Entrenched refusal among vaccine holdouts raises questions about the effectiveness and ethics of mandates.

ROME — Last month Letizia Perna, a 59-year-old estate agent and amateur artist from a seaside town in Tuscany, died from COVID-19. The mother of one was healthy but unvaccinated, and refused both pharmaceutical treatment and intubation.

Perna was one of an increasing number of vaccine skeptics who doctors say are refusing life-saving treatments because of their ideological convictions. Around half of unvaccinated patients arriving in intensive care refuse treatment, with a resulting death rate of almost 100 percent, according to the president of SIAARTI, the Italian association of intensive care doctors.

Alberto Giannini, an anesthetist and a spokesman for the association, said that, while medical staff would not give up on them, a part of the population would likely never change their minds: “People think doctors are part of an international plot, they are afraid of 5G. If they are saying night is day, how do you even start to convince them?”

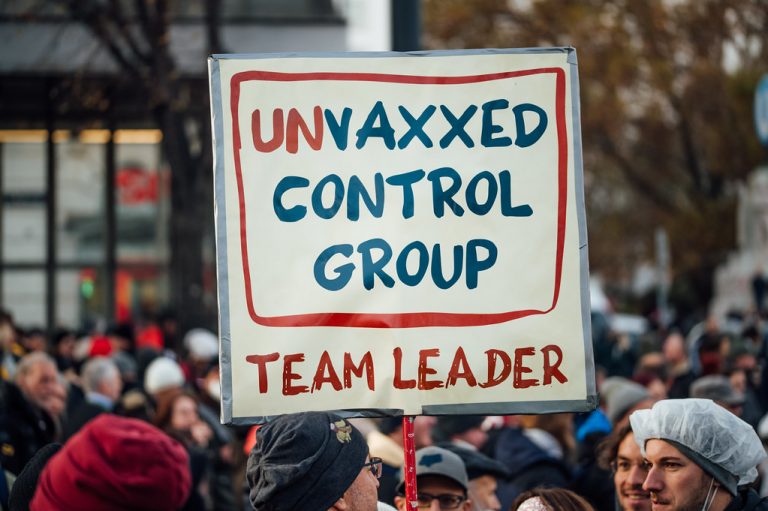

Increased radicalization among a hard nut of holdouts has become an increasing concern as governments — faced with surging infections, lockdown fatigue and the need to protect the economic recovery while safeguarding health care systems — flex their muscles to convince the remaining vaccine-hesitant.

Some are giving up on persuasion and resorting to compulsion in the form of vaccine mandates, raising fundamental questions about whether the limits to civil liberties they entail are acceptable in a democracy. At the same time, the entrenchment of a minority of refuseniks is prompting reflection on the risks to society of polarizing a minority.

Italy has imposed some of the strictest rules, including a vaccine mandate for over-50s, leading human rights organization Amnesty International to urge Rome to ensure its policies are proportionate and non-discriminatory.

European governments are testing alternative approaches. Austria will require all adults to be vaccinated. France has stopped short of obligatory jabs, although President Emmanuel Macron vowed to “piss off” the unjabbed by restricting their rights to socialize. Germany is putting a vaccine mandate to a free vote in parliament, amid concerns about privacy and constitutional rights.

Decisive action

As the first Western country to be hit by COVID-19, and with the highest death toll in the European Union, Italy has every reason to act decisively.

The voracious Omicron variant of the coronavirus, which was discovered only in November and is now the dominant strain worldwide, has caused cases to surge, reaching 180,000 on Tuesday with almost 500 deaths.

COVID-19 patients occupy a third to half of hospital beds in many areas, and one in four intensive care beds in the worst-affected regions. In Palermo this month, two field hospitals had to be opened for the first time. While national vaccination levels, at 80 percent, are above the EU average, coverage is patchy, with a quarter of people unvaccinated in hesitant regions.

Italy has led the charge on vaccine enforcement, becoming the first country in Europe to order vaccines for health care workers and to impose health passes for all workers. The unvaccinated are banned from public transport and nonessential shops and businesses, while over-50s will face a fine if they are not vaccinated.

Beppe Grillo, founder of the 5Star Movement who has flirted with anti-vax positions in the past, says the measures “evoked Orwellian scenes.” And Giorgia Meloni, leader of the opposition Brothers of Italy party, has denounced the mandate as “state blackmail.”

Prime Minister Mario Draghi has explained Italy’s drive by saying that the emergence of new variants like Delta demonstrates the need for higher levels of vaccination. He has called vaccine passes “an instrument of freedom” that permitted the end of lockdowns.

Given that the vaccinated can still catch COVID and infect others, anti-vaxxers often argue that vaccines are ineffective. But, according to Gaetano Azzariti, professor in constitutional law at Rome’s Sapienza University, while vaccines may not be 100 percent effective, a general vaccine mandate can still be justified as long as it reduces hospitalizations.

Where Azzarati sees a problem is when a mandate discriminates between generations: “Having generational criteria is weak,” he said, challenging Draghi’s insistence that Italy’s requirement for over-50s to be vaccinated was not the result of a political compromise and that it was based on science.

Root causes

Human rights and constitutional experts say that vaccine mandates can generally be justified in the public interest, for instance, to protect the health service.

Orsolya Reich, a senior advocacy officer at the NGO Civil Liberties Union for Europe, said mandates should meet four key conditions: They should have a legitimate aim, such as averting the collapse of the health care system; they should be appropriate, offering a safe and effective way to achieve that aim; they should infringe on people’s rights as little as possible; and they should be proportionate.

“So if the vaccine was for a cold [a mandate] would probably not be justified because the problems that a cold causes for society are not weighty enough,” Reich said.

Experts acknowledge that vaccine mandates don’t tackle the root causes of skepticism, such as lack of trust or education.

While making access to restaurants and events more difficult without vaccination can be effective at fighting complacency or indecisiveness, it doesn’t reduce vaccine hesitancy itself, said Jeremy K. Ward, a sociologist and researcher at the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM).

“The real question that governments need to ask themselves is, how important is it to get them vaccinated?” he said. The answer, Ward said, will depend on the age profile of those who are unvaccinated. In some countries, it could be the case that those most at risk of severe disease need to be targeted for booster doses, rather than focusing efforts on getting younger vaccine skeptics to get jabbed. “One thing is for sure — some people will not be convinced.”

For Reich, the human rights expert, even if some individuals are immovable, vaccine mandates can still be justified if they help to avert the collapse of the health care system: “The question is will there be enough people to change their mind to achieve this legitimate aim?”

“No vaccines are 100 percent effective,” agreed Giannini, the doctor, “but they are still important. As a result polio has been eradicated.”

Radicalization risks

Governments also need to weigh the immediate threat to the health care system with the risk of dividing society. Some experts worry that the bluntest tool — mandates — risks further alienating those who already have low confidence in public health institutions. “That’s why it’s very important to make sure that it’s necessary,” said Ward.

In Italy, isolated anti-vaxxers are living in a parallel society, served by alternative transport and shops run by an online network of sympathizers. Hundreds of parents in the northeastern region of Alto Adige, known to German speakers as Südtirol, have withdrawn their children from state-run schools in favor of homeschooling or alternative parent-led schools without masks and vaccines.

Such divisions endanger the social contract and could lead to unrest. Far-right neo-Nazis and far-left anarchist groups have already sought to exploit discontent, organizing protests. In Italy, users of Telegram, an encrypted chat app, have been arrested for alleged plots against Draghi.

There is a risk that desperation could escalate into violence, according to Luigi Corò, who is president of the CMP citizens’ rights group in Venice and a prominent campaigner against vaccinations. Corò asserts that the imposition of vaccinations is actually fueling the spread of COVID, as people deliberately try to infect themselves to gain an exemption from getting jabbed.

“People ask me who has the virus so they can go round to their houses,” he told POLITICO. “They see it as a lesser evil.”

Ashleigh Furlong contributed reporting.